This is part 1 of the Kibbutz Series. You may read the introduction to the series here.

There is a physicist sitting in the university cafeteria. He used to enjoy doing physics. He used to play with it, to do whatever he felt like doing. When he was in high school, he'd see water running out of a faucet growing narrower, and wonder if he could figure out what determines that curve. He didn't have to do it; it wasn't important for the future of science. In fact, somebody else had already done it, many years ago. But it was amusing for him to do it, so that's what he did.

Now, however, he is burnt out. He is stuck in his research—all those problems that are important for the future of science. He doesn't enjoy it anymore. So, he has decided to adopt a new attitude. Now that he is burnt out and that he is not going to accomplish anything anyway, just like he reads Arabian Nights for pleasure, he will start playing with physics, whenever he wants to, without worrying about any importance whatsoever.

So our physicist is sitting in the university cafeteria. Someone is throwing a plate, up and down. He is watching it fly, and he notices something: as the plate rotates it also wobbles, and it does so approximately twice as fast. He has nothing else to do, so he starts to play, to figure out why. And figure out he does.

He shares his solution with his peers. They are confused. "That's interesting", they tell him, "but what's the importance of it? Why are you doing it?"

There are at least two ways to play games. One could be called telic; the other atelic. In telic play (from the greek τέλος --purpose, goal--) one plays a game as a means to its end. In atelic play one plays just for the purpose of continuing to play.

There are infinitely many games, but the list of possible goals of telic games is finite. And usually the same archetypes are repeated over and over again. The most typical include money and social status, which are external to the player; and an inner sense of duty, achievement or meaning, which come from within the player (and which some argue, rather cynically, are just social status in disguise). There are very few games that lend themselves to either purely telic or purely atelic play; most contain a combination of the two. It is usually up to the player to choose how to play.

That fellow sitting in the university cafeteria was not me. That was Richard Feynman, physicist extraordinaire. From that episode of the plate onward, Feynman went on to work on "equations of wobbles", as he put it, which led him to think "about how electron orbits start to move in relativity. Then there's the Dirac Equation in electrodynamics. And then quantum electrodynamics. And before I knew it (it was a very short time) I was 'playing'—working, really—with the same old problems that I loved so much, that I had stopped working on when I went to Los Alamos". "It was effortless", he says, "It was easy to play with these things. It was like uncorking a bottle: Everything flowed out effortlessly. I almost tried to resist it!" And that's how humanity got the Feynman diagrams, and "the whole business" that he got the Nobel Prize for: they "came from that piddling around with the wobbling plate."

If the same thing happened nowadays, he would have written a very viral Twitter thread about it, appearing in several podcasts talking about The Feynman Method To Get Unstuck And Overcome Burnout1. But he was a man from the 1910s and the only thing we got were a couple of nonchalant paragraphs in a book2. Adjusting to publicly-opening-up-to-inner-demons inflation, I am convinced this episode must have been a turning point in Feynman's life.

So what should one conclude about this tale? It is tempting to say something like "look at what Feynman did! He was trying to have fun, and eventually he was utterly productive3 in loosely related important problems . So if you want to be productive, allow some fun once in a while". But the tale, I would argue, is most powerful not as a tale of success, but of searching.

Feynman set out to work on the plate's motion believing it was not important, and that it could never be. He did so against his colleagues' and his own ideas of achievement. So, locally, from his point of view, this fun work was not only disregarding achievement or not planning for it, but even rejecting it entirely.

The way that the same player plays the same game over time may vary. Here is a typical dynamic. Let's say that someone likes to play music. The playing starts out as mostly atelic. There might be some small telic drives here and there, but nothing strong enough to overthrow the main purpose: the joy of continuing to play. At some point, someone says "you know, you could become really good at this". The music player is thus encouraged to go to music school. The grades are good; compared to her peers, she is above average. Little by little, telic play becomes the dominating motivation. Soon there's an audition for an orchestra, a telic game which our player plays and wins. Then comes the salary and the duties associated to that role. By then, the player plays music almost exclusively in a telic way.

After all those years, our player finds it difficult to recover the atelicness. It might be done, perhaps, through tinkering with other instruments, or with other completely different music styles. That tinkering might seem childish and odd from the outside, but it has the most honorable of purposes: to bring back the love of playing for its own sake.

This, I'll make it explicit in case you were reading diagonally, is exactly what happened to Feynman.

In fact, this dynamic is so often repeated that we might as well upgrade it to a couple of Natural Laws.

This is true even if the influences are positive. Here are two from the little story above: listeners giving encouragement, and good grades.

This law also counts as "external" to the game all the influences that come from within the player. After all, a salary is easy to identify as a telic drive, and we can usually quickly build defenses for that. But all the psychological burden that comes from having said to ourselves, over and over again, that our meaning in life is to follow our passion as a violin player? Much less so.

We are encouraged to live our lives telicly. Go study the most practical thing, try to get the best remunerated job, marry someone who is reliable. Even advice that looks atelic, e.g., "go work on what you're passionate about", has the implicit second part "you'll be successful that way"4. And this all might be perfectly good advice! Telic play is the only one that guarantees any result at all. Most atelic play will never amount to any measurable outcome. Feynman's tale is a particularly spectacular example of achievement through atelic play. But Feynman himself is also famous for having done many other fun things that did not precisely get him a Nobel prize. He played the bongos, he urinated upside down to win an argument, and he developed great skill picking his colleagues' locks while working at high-security facilities in Los Alamos, to name a few. The problem with telic advice, then, is not that it's bad advice, but that it's the only advice we ever get.

Atelic play is like a garden that needs active care. We must build fences for the invasive telic species not to conquer it. We must keep tending it in order to grow beautiful, often useless things. And we must try to expand its boundaries by throwing some seeds to the other side of the fence every once in a while. The longer a game goes on, the larger the part of one's life it takes, the heavier the pressure from the surroundings to transmute it into a telic game.

There's only one way I know to tend our atelic gardens. First introspect, then let go. We have to monitor ourselves to see how playing feels. If it is too telic, we need to regain some atelic territory by letting go of some of the goals. Look at Feynman again. He noticed he did not enjoy solving physics puzzles anymore. And he gave himself permission to fail his goals.

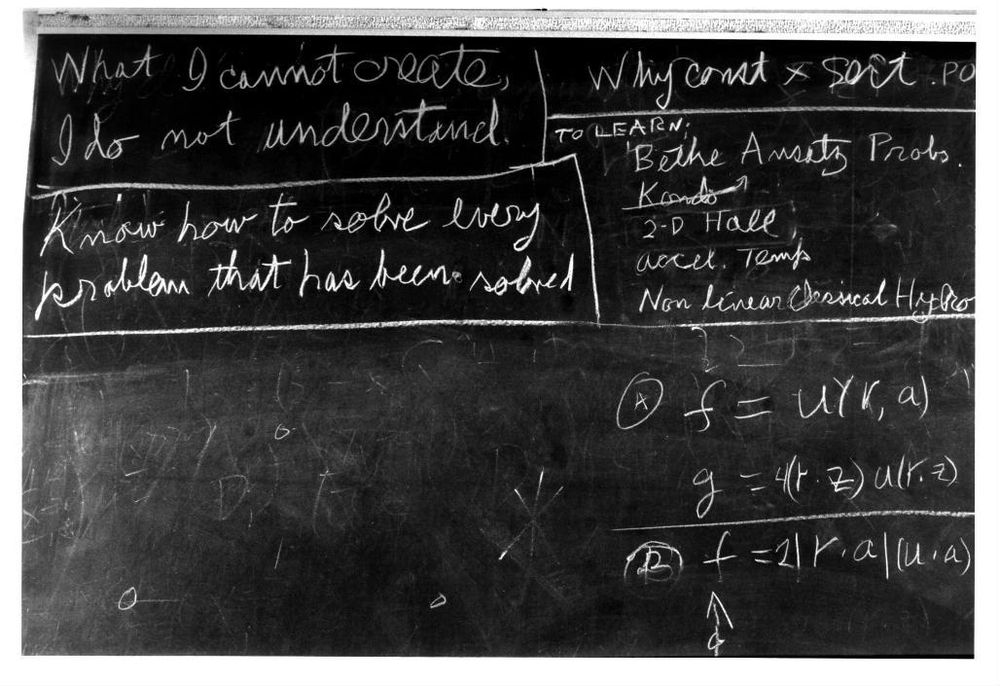

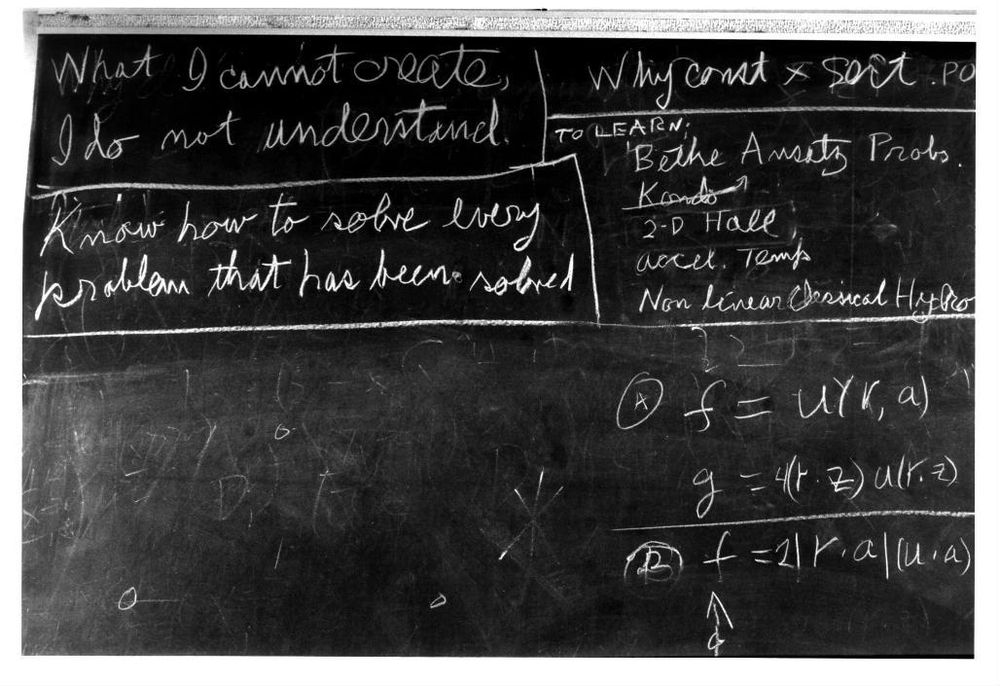

The image that opens up this piece is a fragment of Feynman's blackboard at the time of his death. "Know how to solve every problem that has been solved", reads the second line in tragic child-like calligraphy. There is of course a telos in there, an ambition. But just as there are telic impulses disguising themselves as atelic, the inverse is also true. In order to know how to solve every problem that has been solved, one must not care if it has been done before, and one must find joy in the process of re-discovering it for its own sake. It is in that infinite process of discovering already discovered things that something new may be created.

See you in the next one.

Until then, play more atelic games5 than is strictly necessary.

Iñaki

The irony doesn't escape me: that's exactly what I am doing here.↩︎

This tale is taken from the classic Surely you're joking, Mr. Feynman. You can read the whole plate affair from Feynman's own pen here↩︎

Whatever your preferred definition of productivity is, it must regard a Nobel Prize as pretty good.↩︎

This is, by the way, the same mistake we'd make if we interpreted Feynman's plate tale in terms of the finding and not in terms of the searching.↩︎

This whole ramble about games was inspired by 2 fantastic books. Each one has its own approximate version of what I here call telic and atelic games. James P. Carse's finite and infinite games are somewhat analogous to this, although the striving play and achievement play styles from Games: agency as art are even closer to my categories.↩︎